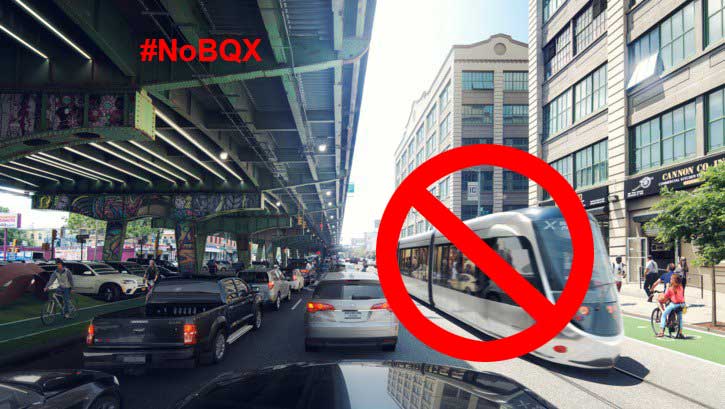

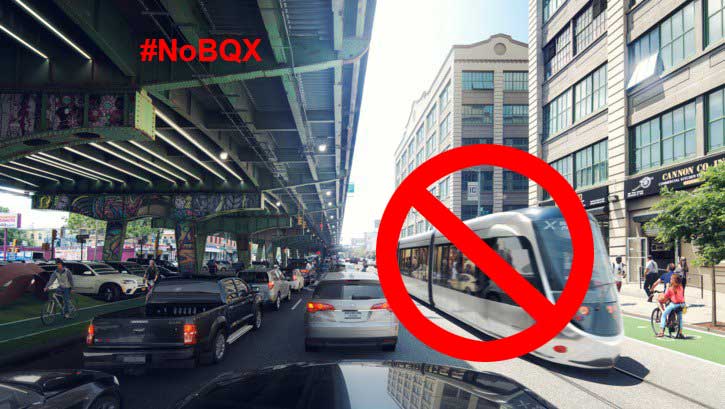

In February of 2016, New York City Mayor DeBlasio unveiled a plan for the city to build a street car/light rail line along the Brooklyn and Queens waterfront in conjunction with an organization known as ‘Friends of BQX”. Since then, there has been no shortage of arguments, some for and many against the proposal. This article will look at BQX from a design perspective – pointing out several large flaws. A future article will go into potential solutions to these flaws.

Before we start, a word on vocabulary: ‘street cars’ and ‘light rail’ are two phrases with more or less the same meaning . They are used throughout this article interchangeably.

BQX and Design

Good design projects often start with a problem statement. Potential problem statements for BQX might be “How can we move commuters from Sunset Park to Astoria in a shorter amount of time?” Or “How can we provide new transit options to the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts?”. Design, of course, is often about coming up with the best possible solution for an existing problem.

BQX is a pre-packaged solution to a problem that is low priority and will have limited impact when compared to other more pressing NYC transit needs.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of the BQX project is that it doesn’t come with a problem statement. BQX is a pre-packaged solution to a problem that is extremely low priority and will have limited impact when compared to other more pressing NYC transit needs. Thus it should be obvious why BQX has not been warmly received by most transit advocates and members of communities it would run through. NYC at the moment has no shortage of well defined commuting problems. These include to completing the entire second avenue subway (including getting started and completing Phase II – which is shaping up to be a quagmire), reopening the Rockaway Beach Branch, a subway extension along Utica Avenue in Brooklyn, the pending L Train shutdown, and significant subway overcrowding, even among the subway system’s alleged “best performing” subway routes.

Good design is never based off opinions-it is based off solid research and irrefutable facts. In this article I will dive into seemingly forgotten NYC history for guidance, and use examples from other cities to illustrate why the BQX streetcar is a very bad idea and waste of the $2.5 Billion dollars it will cost to build.

The 5 flaws in BQX

The BQX proposal suffers from a set of 5 major flaws. This list includes slow travel times, public safety, poor fit with existing NYC transit systems (MTA), being a developer driven project, and limited use cases (potential riders). Let’s look at each, in great detail, keeping design in mind.

1: Travel Times

As others have written, the list of potential transit times put forward by the Friends of BQX simply doesn’t add up. Check them out in the table above, and let’s compare it to existing options:

A. Travel from Red Hook to The Navy Yard via BQX will be 52 minutes. At a distance of 3-4 miles, the train would be slower than a city bus, bicycle or taxi.

B. Friends of BQX state that current travel time from Astoria to Williamsburg is an hour. This is simply not true. Their math seems to be based off going through Manhattan on the N train and switching to the L. Meanwhile, travel time via the N/7/G routing is closer to 40 minutes on a good day.

BQX’s examples are not very precise. Neighborhoods such as Astoria and Williamsburg are not well defined. Astoria could mean anywhere along the N train north of Queens Plaza. It could also mean the R train at Steinway. It could mean as far north and east as the homes near Rikers Island. Williamsburg could mean the waterfront, or it might mean closer to Metropolitan ave and Lorimer street. How about South Williamsburg? East Williamsburg? What is the math for these trips? It is simply unrealistic to boil down the transit time numbers to this simple table when there are many variables to consider.

C. Riding the full route of BQX will take 82 minutes, end to end. This does not compare favorably with taking the N train, which only takes an hour to ride from the far north end at Ditmars to the far south end of Sunset Park at 59th street. Time is money, and it is rare to talk to a commuter who would be willing to spend more time commuting than they already do.

BQX’s travel times are also very optimistic, and based off no known research. How did they arrive at this table? Does it account for rush hour traffic? To the best of my knowledge this data has not been made available to the public.

2: Public Safety

Freight train on 11th avenue in Manhattan

Perhaps the biggest problem with BQX is a seeming disregard for public safety. BQX presents two major public safety issues: grade separation, and the potential need for overhead power lines. ‘Grade separation’ is the separation of train tracks from streets, and overhead power lines may be required to power the trains.

NYC’s Grade Crossings (and the lack thereof)

Presently, NYC only has roughly 2 dozen railroad crossings (depending on how you count the street running freight tracks on first avenue in sunset park, and privately owned railroad crossings such as the new Waste Management crossing off Review Avenue in L.I.C.). Forgotten New York has a handy map and photos of many of these crossings.

Grade crossings (more commonly known as railroad crossings) are deadly. On average, 250 people in the United States die in railroad crossing related accidents per year. None of those fatalities were within NYC in recent years. The few remaining railroad crossings in NYC are largely located in industrial areas, away from the most densely populated neighborhoods. Nearly all of these crossings only see freight train traffic, often late at night. These trains stop at each crossing where a conductor will ensure all road traffic has stopped before the train proceeds.

Forgotten NY Grade Crossing Map

NYC wasn’t always this well off in terms of grade crossings. Before 1876, Park avenue north of Grand Central Terminal was lined in railroad tracks. At the time it was known as ‘Death Avenue’ due to the number of people killed by trains. However, the name “Death Avenue” is more commonly associated with 11th avenue. Before 1934, freight tracks ran right in the middle of city streets (there are few visual remains of this today, though the Terminal Cold Storage building features a massive central hallway that was once a rail siding running through the building off the 11th avenue tracks). Before 1900, there were at least 198 people killed by trains along 11th avenue, including several small children. This eventually lead to the construction and opening of the High Line in 1934.

2004 runaway LIRR locomotive incident in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Such grade crossing incidents are few and far between within NYC due to grade separation.

Atlantic Avenue through Brooklyn also featured trains running along the streets. In 1905 the Atlantic Terminal was built underground and a viaduct to East New York was built in order to eliminate these deadly grade crossings (the tunnel from East New York to Jamaica came later, in the 1930s, as the neighborhoods of Woodhaven & Richmond hill developed).

Other major grade crossing elimination projects included the Flushing and Cooper Avenue crossings in Queens (1935), and the East New York freight tunnel (which proudly proclaims its 1916 ‘grade crossing elimination’ etched in stone right on the face of the tunnel.

Railroads, and the government, were funneling money into eliminating as many grade crossings in NYC as they could. The result is clear: NYC is not a city known for grade crossing deaths. Elsewhere in the United States, there are entire programs dedicated towards educating the public on crossing safety.

East New York freight tunnel was built to separate trains form the streets of Broadway Junction in 1916.

While these examples all pertain to larger railroad tracks, the same holds true for trolley & street cars. Up until the 1950s NYC’s streets contained numerous trolley routes. Brooklyn had one of the largest trolley networks – so much so that the the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team was named after the practice of ‘dodging trolleys’. When trolley cars were first introduced to Brooklyn, there were 107 deaths in the first three years. Eventually the trolley lines were replaced by buses. Many attribute the loss of these trolley lines to a conspiracy from General Motors. This loss of trolley service was definitely a blow to maintaining NYC as a sustainable, eco-friendly city, though we will never know how those trolleys would have performed or evolved for safety in modern times.

Regardless, one cannot refute that BQX goes against NYC’s long history of grade separation between trains, cars and pedestrian traffic. BQX would add hundreds of new grade crossings to some of the most populated streets of Brooklyn and Queens. This will cause significant new public safety issues. Accidents will happen. People will get hurt or worse, and another source of lawsuits against the city will delight Cellino and Barnes.

Not just railroads or ancient history

A quick Google search will find you no end to the inherit dangers of operating light rail trains along and crossing city streets. In Houston, there were 17 accidents in a single month in 2015. In Romania, a light rail train lost its brakes and plowed into traffic, killing one. In Toronto, we see streetcars having accidents with police cars and buses.

The Toronto example highlights an additional cost for the BQX project: training and public awareness. Drivers and pedestrians need to be informed of the dangers of streetcar crossings, and city employee drivers and MTA Bus operators would need a training refresher. Additionally, all first responders will need training on what to should a streetcar get into a serious accident requiring evacuations. This training represents a hidden cost that may not be accounted for yet.

Each time one of these street cars gets into even the smallest accident, there will be service disruptions and significant shutdowns. This will not make for a reliable transportation alternative. Subways rarely get into accidents, and they don’t have to deal with cars, trucks and buses blocking their path.

The bottom line is this: Trains running along streets have a proven record of killing people. BQX reverses NYC’s long history of rail grade separation, and moves the city further from “Vision Zero”. If I could ask Mayor DeBlasio one question about this project it would be “Do you realize your pet transportation project is very likely to injure or kill many innocent people, and are you 100% ok with this?”

Trains running along streets have a proven record of killing people. BQX reverses NYC’s long history of rail grade separation, and moves the city further from “Vision Zero”.

Romanian Street Car that killed one.

Light Rail accident in Jersey City

3: Electricity In The Air, and unproven battery powered trains

Downed power line on Staten Island after Hurricane Sandy.

According to statements made in the February 2016 BQX press conference, the BQX train cars would be powered by batteries, and not overhead power. In order to achieve this, BQX will have to rely on experimental hydrogen-cell battery technology that is not currently used in any other major city. There is currently one small company working on this technology, and their largest installation is a small tourist train operation in Aruba. The railcars used in Aruba have no walls and expose riders to the elements. Tig-m has begun work on a prototype fully enclosed car that looks very much like the BQX railcar renderings, though it is not yet complete or tested. How would this technology perform in NYC’s harsh winters, and under heavier ridership? Will it be ready and reliable in time for the routes opening, or will it cause delays similar to the incline elevators installed on the 7 Extension?

BNSF Battery-powered locomotive fire in Fort Worth, Texas.

For potential answers, let’s look to existing experimental freight railroad technology which is off to a rough start. One company built 50 hybrid diesel-battery powered locomotives 10 years ago. Nearly all of these locomotives were deactivated by 2010, after a mere four to five years in service. They proved to be unreliable, and at least one caught fire. This is a huge safety red flag. It is also a huge budgetary red flag: five years is a very short lifespan for a transit vehicle. The MTA is still running many subway cars that are over forty years old. Obviously the proposed BQX railcars won’t be pushing around tons of freight, but they will need to be sturdy enough to run reliably for years on the often cruel streets of New York City. Battery powered rail vehicle technology simply is not a proven long term solution yet. In the best case scenario, using it will result in huge cost overruns and the necessity to replace equipment often – a cost that taxpayers will be on the hook for. In the worst case, they’ll catch fire and kill riders.

Battery powered rail vehicle technology simply is not a proven long term solution.

What Every Other City Did

Every other major North American city that has opened a streetcar route in the past decade has relied on traditional overhead ‘catenary’ power lines to fuel the vehicles. It is a proven 100+ year old technology that has powered streetcars, light rail and trolley lines around the world. If you’re not familiar with the word catenary, don’t kick yourself – Mayor DeBlasio fumbled the word and had no idea what it meant during the BQX kickoff press conference. You probably have seen catenary wires – they are what powers the Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains, Metro North’s New Haven line trains, as well as several NJ Transit routes.

San Fran light trail trains, powered by overhead wires.

The question here is simple: will BQX be able to run reliably on these battery powered vehicles, or will overhead power lines be required?

If the power lines are needed, they will add yet another danger to the streets of Brooklyn & Queens. Let’s look again at Jersey City, where a dump truck hit their light rail’s power lines in May of 2016. Fortunately no one was hurt but service was disrupted for over 24 hours. Over in Dublin, a downed catenary line injured at least one person last year. There are dozens of other examples from around the globe.

Dump truck that took down Hudson Bergen Light Rail power lines in May of 2016, resulting in a severe service disruption and immediate danger of downed power lines.

Using overhead power for BQX would once again march against lessons from NYC history: During the winter of 1888, NYC was hit with a severe snow storm that resulted in downed power lines and deaths. The storm played a large part in overhead power lines being banned from Manhattan. Brooklyn and Queens at the time were significantly less populated. Today, parts of the waterfront of both boroughs rival the population densities in Manhattan. Would it be acceptable to string high voltage power lines over these outer boroughs streets when the same was banned from Manhattan in the 1880s?

Today, there are few overhead power lines close to Manhattan, so most New Yorkers have never truly known the danger they present. However, In the furthest reaches of the city, homes are still wired to receive electricity from these power lines, which frequently fall during storms. After Hurricane Sandy left much of Staten Island in the dark, Staten Island Live stated that we should be pushing utility companies to bury these

lines in order to create a more resilient city.

Overhead power lines were banned from Manhattan in the 1880s

Both streetcars and overhead power lines would introduce new dangers to a densely populated part of NYC. This should be discussed openly, and loudly. There is also the need to perform serious testing of the battery powered streetcars to ensure they can perform reliably on the crowded streets of NYC, in all types of extreme weather, and that they are durable enough to last at least a decade or two of use before needing to be replaced.

3: Limited Ridership Potential

BQX is projected to have a fairly small amount of daily riders. By the Friends of BQX’s own estimations, the train will only have 24,500 estimated daily riders to start, growing to maybe 48 thousand in 2035. As many transit advocates have already stated, there are existing NYC bus routes with higher ridership today.

Worst, the BQX route duplicates existing transit routes, none of which have ridership that comes close to rivaling the busiest NYC bus routes. Why spend billions of dollars on something with such low projected ridership numbers?

Utica Ave Subway extension – map courtesy Vanshookenraggen

Meanwhile, entire neighborhoods such as the Utica ave corridor, Pelham Parkway / Fordham Rd in the Bronx and the neighborhoods along the former LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch have to rely on buses. The Utica avenue corridor was promised a subway route in 2015. The former Rockaway Beach Branch is finally being studied for reactivation, though an ex NYC Parks commissioner who ignored Queens parks during his decade on the job is trying to make sure the route never sees another train again.

There is a very compelling argument to be made for new transit route prioritization. When comparing potential ridership to other much needed transit routes, BQX would fall far behind the existing laundry list of significantly more useful transit projects.

4: Fossil Fuels

If BQX is forced to rely on overhead power lines, it will be largely dependent on fossil fuels. More than 70% of NYC’s electricity is powered by fossil fuels. NYC is increasingly feeling the affects of climate change every year, and continuing to reduce our carbon footprint (beyond more efficient buses and taxis) is extremely important. While other cities (such as Vancouver) banned non-hybrid taxis, reducing fossil fuel consumption isn’t very high on NYC’s current priorities. This is extremely unfortunate and a sad commentary on our prioritizes and those of our elected officials. We need to start electing people to the city council who take this matter significantly more seriously.

5: Limited Subway Connections

The originally proposed route does not link up with the F, N and W in Queens, or the F, J/Z or L subway lines in Brooklyn. Free transfers from MTA buses and subways to BQX will probably not exist. Again, BQX goes against the tide of NYC history by reversing advances made in the 1990s to eliminate all ‘two fare’ zones within the city. This is literally a huge step backwards in progress for keeping NYC affordable and sets an extremely dangerous dangerous precedent.

By now you might be wondering: Who came up with the idea for BQX? How have they missed all of these huge design flaws?

Developer Driven, not Commuter Driven

The origins of BQX go back long before DeBlasio’s February 2016 press conference. In 2014, the NY Times ran an article discussing much of what made it into the 2016 proposal. The article espouses the increases in real estate value that constructing a streetcar would bring. This idea eventually found a champion in Jed Walentas, the CEO of Two Trees Management (owners of domino sugar high rise construction site). It gained further support from the real estate industry via Doug Steiner, chairman of Steiner Studios in the Navy Yard, and the Durst organization, developer of the proposed (and currently stalled) Hallets Cove development site in Astoria. At least seventeen of original twenty-five board members are real estate developers or are associated with real estate. Only three of the original board members have significant transportation experience, two being former MTA chairmen. The MTA, it should be noted, owns large real estate holdings throughout NYC.

Rather strangely, One of the board members is a pastor who was involved in a violent altercation two years ago.

It has recently been reported that the real estate developers have contributed $245,000 to DeBlasio’s non-profit. While this may be legal, it is an obvious game of developers buying the mayor’s influence.

I am by no means the only person to have noticed the lopsided membership of the original board of directors.

Politically, another huge motivator for the BQX project is the current rivalry between Mayor DeBlasio and NY State governor Cuomo. The BQX project would be largely built along NYC city streets, which the Mayor controls. The MTA is a state-run organization, and Cuomo has already blocked several of DeBlasio’s initiatives which required state approval. This political squabbling is a direct cause of the BQX plan being presented as a transit solution instead of focusing on the subway extensions and overall service improvements that the city desperately needs. NYC would be far better off if Cuomo and DeBlasio could put aside their egos and do right by NYC commuters. Continued failure to do so will hopefully result in unfavorable ratings for both come election time. New Yorkers don’t need this political drama. We need real transit solutions.

I have seen no evidence that anything resembling a proper design process took place before BQX was introduced to the public.

Going back to design 101, this simply is not how a product should be designed. Consumer goods manufacturers conduct extensive research before introducing a new product. They want to make sure their investment satisfies the needs of their customers as best they can. I have seen no evidence that anything resembling a proper design process took place before BQX was introduced to the public. There were zero designers or even city planners on the original board of directors. If there was any customer research performed before the introduction of the BQX plan, it has not yet been shared publicly.

What is the problem BQX is trying to solve? Is BQX meant to be an actual transit solution, or something else? The makeup of the board of directors suggests that real estate interests are more important than NYC commuter interests. The projected cost of BQX – 2.5 billion dollars and rising – is steep for a transit solution that doesn’t seem to solve any major commuters problems. This money could be applied to any number of more pressing transit projects affecting actual commuters today.

Mayor DeBlasio was famously quoted as saying “people are going to take this, just to take it”. As Alissa Walker of Gizmodo so perfectly stated: “If it’s designed for people who will “take this, just to take this,” that’s not really solving problems for people”.

Conclusion

From a design perspective, BQX simply doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t solve actual commuter problems, it adds significant new dangers to the streets of Brooklyn and Queens, and it may add to NYC’s overall carbon footprint. It goes against NYC’s long history of attempting to make streets safer, and would likely create a new ‘two fare zone’ system that adds an extra burden to NYC’s commuters.

Next week, I’ll be posting an article that looks at potential solutions to all of these design flaws, and present grand ideas on how BQX could be vastly improved to serve the needs of all New Yorkers. Some of my ideas will be obscure, while others will hopefully make us wonder ‘why aren’t we doing this already?”. I have no doubt most of the ideas will never come to light, but I would be remiss as a designer to only document flaws without presenting any solutions. In conclusion, NYC has huge existing transit and commuting problem, which the present design of BQX does absolutely nothing to rectify.

Leave a Reply